Goodbye, Cuba – 1990

Nevermore would someone call me “terrible,” “the corruptor of minors,” “sexually obsessed,” “the defender of women,” “the queen of condoms,” or, simply, “Monika of sex education,” as I’ve often been called in place of my proper name. Nevermore would I have to answer hundreds of letters or telephone calls from the most remote places in the country coming from people who belonged to the most diverse social strata, representing a spectrum of extraordinarily versatile sexual ideologies, quintessentially contradictory, and, frequently, truly folkloric.

In The Beginning – 1961 in Rostock, Germany

“If you insist on wanting to marry this man, you will see your study dreams ruined, and you’ll end up cleaning public toilets! You’ll NEVER get out of East Germany! You’ll NEVER get married to this man, you’ll NEVER, NEVER, NEVER . . . !”

The up-to-now sympathetic official had become a ranting ogre. He sounded like a broken record. He was so furious that he couldn’t stop shrieking. Never before had I been insulted in such a way; never before had I felt my university career in such danger. My sane, solid world, my luminous future was crumbling.

Culture Shock – Arrival in Havana, 1962

We approached Havana around midnight. From port side I could see the Malecón, the boardwalk of Havana. The lights of hundreds of cars, from the distance, looked like an enormous sea of thousands and thousands of fireflies that gave the impression of lightning flashes along the avenue. A starry sky competed with the electric illumination of the city. It presented us with an extraordinarily beautiful painting. I had never seen a metropolis from the sea, much less one that was so impressively immense, extensive, and bathed in a sea of lights. My first vision of Havana: never again would I see it so beautiful, so gigantic, and at the same time so welcoming.

They all must have been terribly disappointed. I didn’t fulfill any of the requisites of a wife for a person of such stature as my captain. In place of the obligatory mane of hair, I had a short haircut. Instead of high heels, I wore flat sandals. I wasn’t wearing makeup, not even mascara. I didn’t have on a tight skirt, just a loose one, and I was wearing a white blouse that looked like a primary school uniform. Nor did I wear gold chains, rings, bracelets, earrings, or loops.

The Missile Crisis and Birth of Our First Son

I didn’t know how not to worry, how to believe that everything would work out, since he had just told me that we were at war. How did I end up in this crazy country?

Before my son emerged from his sanctuary, I spent the last minutes in agony and exhaustion, desperately applying the short, quick breaths of a panting dog, which I had learned in the classroom of lies. I believe that a high-performing athlete, in a year of training, didn’t expend the energy I did in my eight hours of labor. When the final contractions appeared, the obstetrician made a triumphal entrance into the room.

Our Family Will Be Complete

“He’s dead; there’s no remedy.”

I was losing consciousness, but I woke up after a while, in time to see them place an injection into the umbilical cord vein, which had the expected effect. The purple bundle contracted and suddenly screamed in horror. From then on, he didn’t stop screaming until he was placed in the crib. I lost consciousness several times. I had made a fierce effort and no longer had any energy, but now I could rest, knowing that my son was alive.

I Am A Cuban Woman

I was granted the condition of a Cuban citizen with the delivery, in a solemn act, of the citizenship certificate. I was now aplatanada, a native. I felt Cuban, with all the responsibilities, duties, and obligations that were implicit in this condition.

In my unofficial life, I would sink up to my neck in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, and would swim out to sea where there were no witnesses, combining physical exercise with the spiritual, ventilating the contradictions, conflicts, doubts, desperation, hope, fear, but also daring and confrontation.

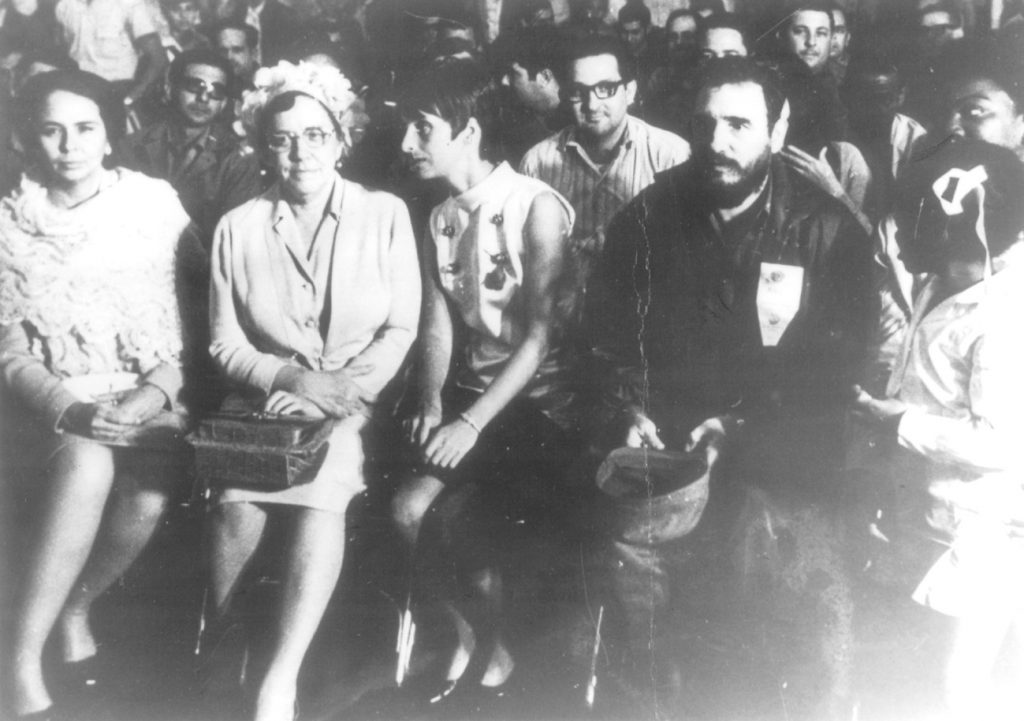

An official at the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC)

Every year without fail, the FMC held a plenary session that was attended by representatives from all the provinces. Its purpose was to analyze and discuss the fulfillment of the organization’s work plans. In one of these plenaries, we received a visit from a member of the Politburo of one of our sister socialist countries. I was asked to be her interpreter. It was very difficult to translate the debates of the federadas, the FMC women. A person accustomed to the procedural rigidity in her own country’s assemblies could be overwhelmed at seeing and listening to the multitude of women who were talking, discussing, intervening, and—horror!—interrupting without recognizing any internal order, without any established discipline that regulated how the activity was run.

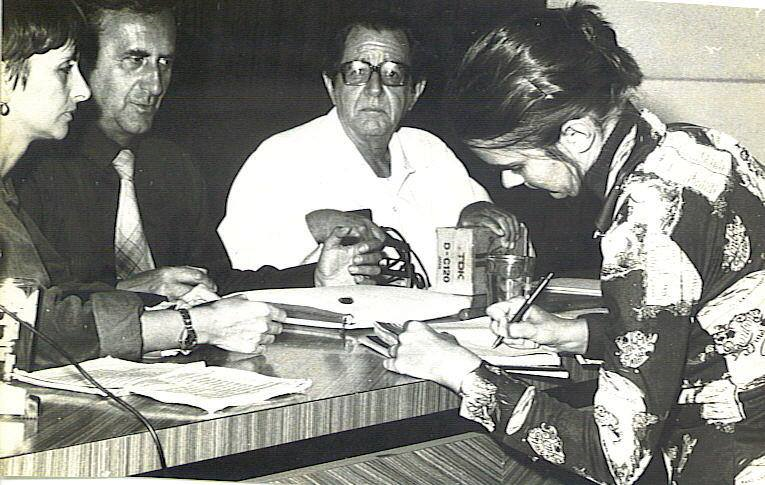

Becoming a Sex Educator

Destiny provided a horrifying car accident that fractured my neck and almost sent me to the Great Beyond to mark the beginning of a new stage of my life in Cuba: a life dedicated to sex education, a life of enormous sacrifice and great professional satisfaction.

It was extraordinary luck that the National Sex Education Work Group (GNTES) was organized at a high level of the government.

Formally, GNTES was attached to the National Assembly of People’s Power, but I reported directly to Vilma Espín Guillois, la Presidenta, the President of the Federation of Cuban Women, Raúl Castro’s wife and the country’s First Lady (in the absence of an official wife of Fidel Castro), a member of the Council of State and the Politburo of the Communist Party of Cuba. La Presidenta belonged to the small circle of people who actually made the country’s decisions.

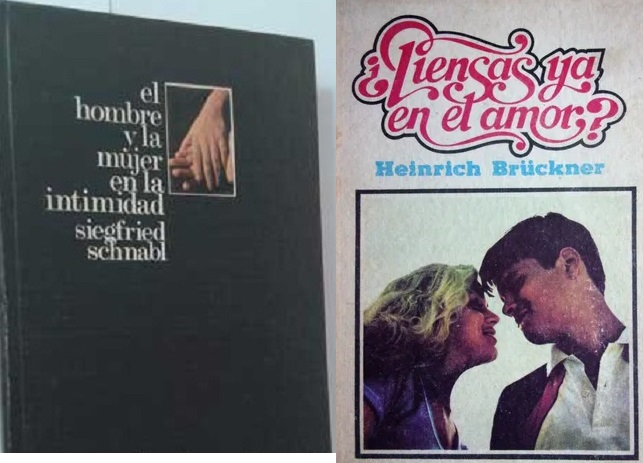

Books On Sexuality Hit The Mark

Fortunately, a second edition of Man and Woman in Intimacy was produced years later, reaching a total of 150,000 copies.

With the second, revised and updated, edition, we also managed to circumvent the censorship. We handed over the manuscript without giving the detractors time to mutilate it, and so it happened that for the first time in Cuban history, a book was published dealing in very broad terms and with a scandalously modern approach with the subject of homosexuality.

In 1982 the book Are you Now Thinking about Love? came out. Two nude photos, one of each sex, managed to survive the censorship, but not the childbirth photos. Even so, we were happy with the result. In numerous letters to the publishing house, readers expressed satisfaction and joy that such a comprehensive book, so full of information for adolescents, had finally been published. The 100,000 copies of the first edition sold out right away. In 1983, another 150,000 copies were printed. Even so, many young people complained because they hadn’t been able to get a copy. They requested a new edition. The Juventud Rebelde newspaper and the monthly magazine Muchacha published the book in chapters.

Monika, Queen Of Condoms

A few days later a wave of requests began. The hospital dermatologist demanded a whole palette of condoms for her special area of sexually transmitted diseases, because for the first time since the beginning of her career, she saw the possibility of achieving the definitive cure of her patients with gonorrhea, protecting them from reinfections by using quality condoms.

The effective blow had been dealt. The condom, which in Cuba until then had been unanimously and irrationally rejected, came to enjoy wide acceptance. And with this act, I earned the nickname “Mónica, la Reina del Condón.”

Star Of Radio and Television

A veritable tidal wave of sex education flooded the island in the 1980s. Everyone wanted to participate, and sex education was all the rage. Newspapers and magazines held competitions to see who best informed, instructed, and educated Cubans about sexual matters. Radio and television followed.

“I’ve received complaints about the program,” she said. “They say you’re talking about indecent things on the radio; for example, that you speak in great detail about masturbation.”

La Presidenta repeated her concerns but then implied that the reaction of the audience was tremendous, that the program has already become an institution. She wavered between approval and disapproval. I interpreted this indecision in my own way: in my favor, as a call to continue my program as it had been until now. And so I proceeded.

Six months after starting it, they informed me that my program on sexuality had been declared “Star Program” of Cuban radio.

At The Peak of my Career

The School of Medical Sciences gave me one month to prepare and present myself before a commission to take the state exam to become a full professor, which was a requirement if I were to continue teaching classes to health professionals and medical students.

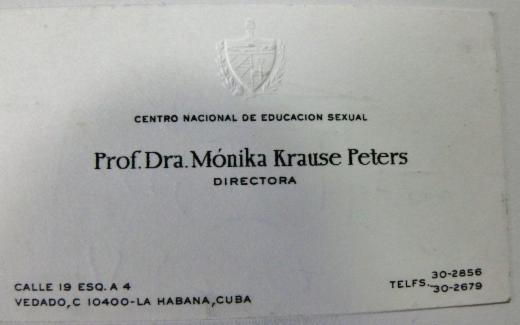

In 1988, the National Sex Education Working Group (GNTES) became the National Center for Sex Education (CENESEX), in recognition of the importance of our work and the magnitude of its impact. CENESEX was also given a broader mandate, particularly for research work and the training of professionals. I was appointed the first director of CENESEX, a position that I filled with all my energy until the day of my return to Germany.

My Last Stand Against Institutionalized Homophobia

The publication of the interview in Alma Mater in 1990 cost me severe disapproval for violating strict, explicit orders. But it filled me with satisfaction to see that it had unleashed a change, a process of critical discussion of the homophobic policies in force throughout the country. The days were numbered for the infamous homophobic resolution of the First Congress of Education and Culture in 1971.

The Circle Is Closed

Looking back at my life in Cuba and my professional career, many have asked me (and I have also asked myself) whether the sacrifice was worth it—Was it worth giving thirty years of my energy and youth to Cuba? Was there anything left of my timely, small, ephemeral contribution to the cause of women’s equality in Cuba, of my fight against machismo? Did I do anything more than sprinkle a few drops of water on the fire?